A new front just opened in the US-China trade war, and it wasn’t good news for countries who do business with both.

China reportedly instructed South Korean companies to stop exporting defence-related products to the United States if they contained rare earth products from China.

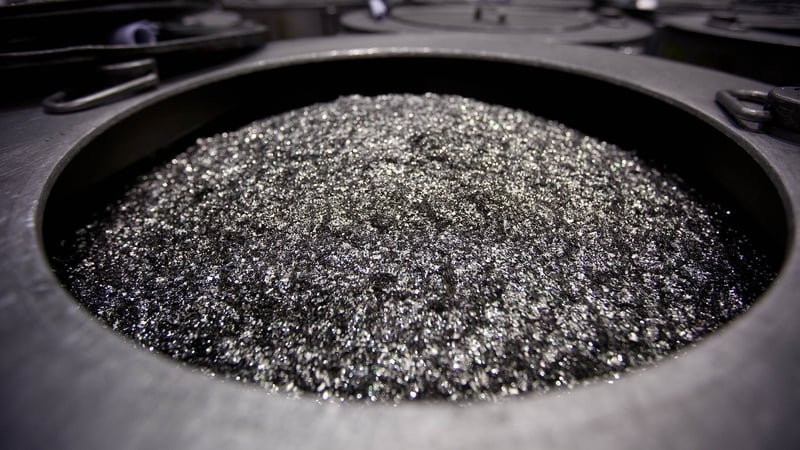

Those are the natural metals – 17 elements on the periodic table to be precise – that go into everything from smartphones to satellites, deemed critical for renewable energy sources like solar panels and wind turbines as well as advanced weapons systems, robotics and rockets.

And China produces most of the world’s supply of them.

According to Korean press reports, China warned that it may halt exports of rare earths to South Korea altogether, if the ban was ignored.

“It’s shocking,” said Julie Michelle Klinger, professor of geography at the University of Delaware and author of Rare Earth Frontiers.

“Under a liberal free trade regime, what right does one country have to tell another what it does with its business and trade transactions?” she said, adding, “I think it’s pretty clear that that’s not the world that we live in anymore.”

Indeed, in retaliation for US President Donald Trump’s 145% tariffs on Chinese goods, China was quick to play its ace card: ordering the restriction, through a licensing system, on exports of seven heavy rare earths and the high-performance magnets that contain them.

It was a clear sign, observers said, that Beijing was willing to weaponise its dominance of the sector.

“China made that list strategically,” Mel Sanderson, director of American Rare Earths told Reuters news agency. “They picked the things that are crucial for the US economy.”

This week Tesla CEO and close presidential adviser Elon Musk, who maintains deep business interests in China, acknowledged it was causing problems.

He told Tesla investors on Tuesday that a magnet shortage could hold up the production of his AI-powered humanoid robots, designed to carry out mundane tasks like housework, serving drinks and assembly line production.

And he’s not the only one worried. Because while these magnets are handy to operate the arms of a tea-carrying bot, they are also to be found in the engines of fighter jets.

Handwringing over global dependency on China for critical minerals has been going on in Washington – and indeed Brussels – for many years.

Soon after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the deputy prime minister of Sweden, Ebba Bush, said Europe’s dependency on Russian gas would “seem like a nice summer breeze,” compared with reliance on China for the green energy transition.

Critical mineral dependency quickly rose to the top of the Trump administration’s agenda with the White House pushing for a deal with Ukraine for premium access to theirs and threatening to annex resource-rich Greenland for the same reason.

But one detail that is often left out of the telling is China’s near total monopoly on processing.

In other words, countries can extract these resources from their own soil – say in Ukraine or Greenland – but they would still need to send them to China for separation and refining.

Developing mining and processing capabilities requires “a long-term effort,” meaning the United States will “be on the back foot for the foreseeable future,” concluded a recent report by the Centre for Strategic and International Studies in Washington DC.

Policymakers should have seen this coming, analysts said.

“I hate to be the person who says this,” said Ms Klinger, “but I remember saying over a decade ago, if we should have a rare supply chain crisis, it would be entirely avoidable”.

So how did the world get to this point?

Why did the US – once the king of mining and refining – give its industry away?

The answer is very simple, according to Ian Lange, associate professor of mineral economics at the Colorado School of Mines: it wasn’t that profitable.

“I would have said, it was a conscious decision to get rid of a low-value industry,” he told RTÉ News.

It’s also heavily polluting.

According to a study published by the Harvard International Review in 2021, for every tonne of rare earth produced, the mining process “yields 13kg of dust, 9,600-12,000 cubic metres of waste gas, 75 cubic metres of wastewater, and one ton of radioactive residue”.

For many years, it made sense for the US, Europe and others to outsource to China, which ultimately, through state subsidies, weaker labour and environmental regulations, R&D investment as well as sheer industrial scale could – as in other manufacturing sectors – simply do it cheaper.

The strategic vulnerability of this arrangement was first laid bare in 2010 when China cut exports to Japan over a territorial dispute involving a fishing trawler.

China reversed the ban when the World Trade Organization ruled against it.

But the shock reverberated around the world.

It drew comparisons with the energy crisis of 1973 when Arab oil-producing nations in the Middle East cut off exports to the US and other countries in retaliation for their support of Israel during the Yom Kippur War.

By the time the embargo was lifted, global oil prices had soared more than 300%.

The power of energy-rich nations to exert leverage over energy-hungry ones was not lost on the former Chinese leader, Deng Xiaoping.

“While the Middle East has oil,” he famously declared on a visit to one of China’s biggest mineral mines, “China has rare earths.”

But there’s a crucial difference, according to Ian Lange.

Oil deposits are concentrated in a few key regions. But “rare earths” is a misnomer, because they are really not that rare.

“Everyone has good dirt,” he said.

The question is whether countries like the United States are serious about cultivating their homegrown industries – and their accompanying environmental costs – and crucially, if they can become profitable in a market dominated by cheaper alternatives from China.

In the 15 years when rare earths made the news over the Japan crisis, he said, the industry is not that much further along.

“It’s an economic issue,” he said, “you’re competing against a subsidised monopolist who doesn’t care about profits”.

That’s why China’s export restrictions on rare earths in retaliation for Trump’s tariffs “is a gift to Western industry,” Ms Klinger said.

Entities outside of China have been trying to build up their rare earth supply chains for years, she said.

“They just haven’t been able to compete with China”.

Nevertheless, some diversification has taken place.

Last year, the Australian mining company Lynas opened its first rare earth processing plant in Western Australia.

In the United States, California’s Mountain Pass mine in California’s Mojave Desert, shuttered in the 1990s after toxic waste spills, reopened in 2018. The mine is now operated by MP Materials, which is also building a magnet-making facility in Fort Worth, Texas.

And in Europe, there are facilities in Estonia and Sweden, while Belgium chemical company Solvay just launched a rare earth magnet production line at its plant near La Rochelle, France

By 2030, it is expected to meet 30% of Europe’s demand for high-performance magnets.

But, in the 40 years since the rare earth industry began moving there, China has developed the technological know-how that other countries simply don’t have and will struggle to build up in time.

In 2023, Beijing announced restrictions on foreign access to that technology in a move seen to be, in part, a retaliation for a Biden-era ban on sales of US cutting-edge computer chips to China.

But while China is prepared to use rare earths as part of its trade war toolkit, it’s also wary of going too far.

Holding the world to ransom risks undermining its dominance of the industry – by encouraging alternative sources – and damaging its reputation as a trading partner, analysts said.

“Doing something dramatic like halting exports or anything that slows down the flow of material out of China has implications for firms that have invested in China,” Ms Klinger said.

“What happens if they leave?”

China does not want to end up with a labour unrest problem, she added.

But for firms – and indeed countries – doing business with both China and the US, Beijing’s warning to South Korea this week was a reminder they could find themselves in the crosshairs of an intensifying trade war.

And critical minerals will remain a key battleground.